Denver University Web Central

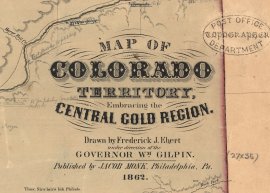

The map includes a high level of detail–so much so that we might question its reliability. After all, much of this topographical detail was simply unavailable in 1862, though in some areas it comes fairly close. You may also notice a rather large (and non-existent) lake in south central Colorado, within Costilla County. Again, an indication that much of the topography of the more remote areas was speculative and aspirational. But that aspirational aspect was part of the very goal of the map: William Gilpin had a long history as a booster for the region, and you can see his enthusiasm in the title of the map itself, “embracing the central gold region.”

The map includes a high level of detail–so much so that we might question its reliability. After all, much of this topographical detail was simply unavailable in 1862, though in some areas it comes fairly close. You may also notice a rather large (and non-existent) lake in south central Colorado, within Costilla County. Again, an indication that much of the topography of the more remote areas was speculative and aspirational. But that aspirational aspect was part of the very goal of the map: William Gilpin had a long history as a booster for the region, and you can see his enthusiasm in the title of the map itself, “embracing the central gold region.”

I also like the way the Ebert-Gilpin map captures the fragility of Denver at the moment that President Lincoln replaced Governor Gilpin with John Evans. Evans had a strong reputation within the Republican Party–indeed he founded the party in Illinois–and had been heavily involved in railroad investment in and around Chicago. He also founded Northwestern, and is the namesake of its home in Evanston.

When Evans arrived, Denver was facing a declining population, serious conflicts with the Arapahoe and Cheyenne tribes, an evaporating mineral rush, and an uphill battle to get a railroad to connect the town to the outside world. Indeed, take a look at the detail below, and notice that the post office has written “630 miles from Atchison” just below “Denver City, ” an indication of just how far the small town was to the nearest major mail outpost toward the east.

The map also includes a large “Indian Reserve” to the southeast of Denver, a product of the recently concluded Treaty of Fort Wise. This is especially important information given the ongoing (and escalating) conflicts with the plains tribes and Denverites during the Civil War. This is a complex history that others have covered well, especially Elliott West in Contested Plains. Here I simply want to note the presence of this “Reserve” on the map–which is itself rare given that it only existed between 1861 and 1864.

The map is the first to show counties in Colorado, and in my view suggests a level of stability and political organization which is utterly at odds with the turmoil “on the ground.” Carl Wheat, in his exhaustive history Mapping the Trans-Mississippi West, calls the map “imposing, ” and it certainly conveys a sense of permanence in a territory which is less than a year old, and which has only a few thousand inhabitants. Notice the number of towns that have been introduced, and subsequently deleted (all of the notations on this map would have been made within just a few years of its being printed).

You might also like